| Site home page | Conference home page | Discussion |

Structural pathways

of electron transfer via tunnelling and

van der Waals in the

cytochrome f-plastocyanin cpmplex

Mário Fragata

Université du Québec à Trois-Rivières,

Département de chimie-biologie,

Section de chimie, Trois-Rivières, Que, G9A 5H7, Canada

fragata@uqtr.uquebec.ca

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methodology

3. Results and discussion

3.1.

Molecular structure of the docked interface in cyt f-pc

3.2.

Structural pathways of electron transfer in cyt f-pc

3.3.

Intramolecular electron transfer: Tunnelling effect

3.4.

Intramolecular electron transfer: Van der Waals contact

4.

Concluding remarks

5.

Abbreviations

References

Acknowledgements

Last page

A study was undertaken of the molecular pathways of electron transfer

in the cytochrome f-plastocyanin (cyt f-pc )

complex. The calculated centre-to-centre distances of electron

transfer (ETd) are (i) 7.2 Å from the Fe-atom and the tyrosine

1 (Y1) in cyt f, and (ii) 5.9 Å from Y1 to the Cu-atom in

pc. Within the plastocyanin core, ETd = 7.0 Å between

cysteine

84 (C84) and serine 85 (S85) and 5.2 Å between S85(OH) and tyrosine

83 [Y83(OH)]. A calculated alternative route of electron transfer

in pc is between C84(SH) and the p-electron

system in Y83 where ETd is ~7.3 Å. On the other hand,

the electron transfer distance between the Cu-atom and C84(SH) is approximately

2.6 Å, i.e., the coordination distance from the copper-atom to the

SH group in C84. ETd = 2.6 Å is clearly quite small in

relation to the 5 to ~7 Å determined for the various electron transfer

pathways in cyt f-pc. In this respect, it is noted first that electron

transfer distances higher than about 5 Å are in general a good indication

of electron transfer occurring by tunnelling efffect, that is, by a quantum

jump from one electronic state to another. On the contrary, it is

reasonable to assume that electron transfer reactions at distances as small

as 2.6 Å might simply take place via van der Waals contacts.

This is a convincing argument to suggest the coexistence of different molecular

mechanisms of electron transfer in the cyt f-pc complex. Such coexistence

of molecular states has far reaching consequences

so far as it presupposes the function in cyt f-pc of adiabatic and non-adiabatic

electron transfer processes which have different temperature dependence,

or requirements.

Biological electron transfer between redox proteins is

of fundamental importance in such speciallized organelles as the chloroplasts

of green plants and algae, or the mitochondria of most organisms.

In short, these molecular systems are responsible for the function and

the

efficiency of the photosynthetic and respiratory processes in living

cells. In nature, this question has been solved with a complex, yet

elegant system of molecular pathways leading to a remarkably efficient

transfer of electrons through molecular distances that can be about 20-25

Å, or longer (see data discussed in [1,2]). An interesting

aspect of this question is that the biological electron transfer devices

seem in general protected against difficulties brought about by energy

losses of various types. For example, electron transfer decay due

to inadequate molecular rearrangements in the structural pathways, or to

electron back reactions. This question has always been intriguing

since the construction of efficient man-made batteries for solar energy

conversion into chemical or electrical energy is quite often plagued with

difficulties inherent to energy losses due to the back reactions.

In this perspective, understanding at the molecular level the electron

transfer mechanisms as those taking place in the photosynthetic membrane

of the chloroplast might eventually foster our comprehension of how to

build artificial electron transfer devices with efficiencies comparable

to those usually observed in nature.

The study of the biological electron transfer mechanisms

has made the object of a very large number of works (see, e.g., [2-10]).

For the purposes of the present work, it is noted that in oxygenic photosynthesis

the cytochrome b6f (cyt b6f) complex transfers electrons

between photosystem II and the P700 reaction center of the photosystem

I complex [9]. From cytochrome f (cyt f) in cyt b6f to PSI,

the electrons are shuttled by the mobile redox carriers plastocyanin (pc)

and cytochrome c6 (cyt c6) [9,10]. In several cyanobacterial

species, cyt c6 is the only electron carrier but in other cyanobacteria

and in certain eukaryotic algae this role is played by either cyt c6 or

pc [3-7]. In those cases, the biosynthesis of either pc or

cyt c6 is determined only by the availability of copper in the environment

or in the culture medium. In higher plants, however, the genes for

cyt c6 are not present, meaning that pc is the sole electron carrier between

the cyt b6f complex and P700.

In spite of the many efforts to solve the electron transfer

question in the cyt f-pc system, the molecular mechanisms and structural

pathways of electron transfer in the photosynthetic membrane are yet far

from being clearly understood. The purpose of this study is twofold.

First,

the purpose is to model the most relevant structural pathways of electron

transfer in the cytochrome f-plastocyanin (cyt f-pc) with the intent of

devising a structure-function model electron transfer by tunnelling effect

or via van der Walls contacts. Secondly, the object of this

work is to use semiempirical mathematical expressions of electron tunnelling

to predict experimental rates of electron transfer, i.e., the electron

tunnelling probabilities. In this context, the present study showed

that the most efficient structural pathways of electron transfer in the

cyt f-pc complex are those characterized by small differences (V-E) between

the kinetic energy of the approaching electron (E) and the energy (V) of

the barrier above E, i.e., dV (=V-E, or the barrier height). That

is, dV is found to be approximately 0.1 eV at tunnelling distances between

5 and 7 Å.

In the determination of docking configurations and other molecular modellizations, we took into account the data obtained from chemical cross-linking, chemical modification of amino acid residues, and the effect of mutations on the reactivity of different pc and cyt f forms [11-17]. Special attention was also given to the structure of the interfacial medium between the heme in cyt f and the surfaces of docking of the electron acceptors (pc). As a rule, we took into account any structures in the surfaces of docking that may influence the donor-acceptor couplings (see discussion in [18]) in spite of the fact that some of those amino acid residues are not directly involved in the activity of the cyt f-pc complex. We have thus minimized the stereochemical hindrance at the interacting surfaces, but making sure at the same time that the molecular complementarity that is needed for efficient docking and electron transfer was preserved.

The atomic coordinates of cytochrome f and plastocyanin

were obtained from the Protein Data Bank [19,20], that is, 5pcy.pdb

(plastocyanin)

and

1ctm.pdb (cytochrome f). The cyt f-pc complexes

was modelled using the computer graphics program TURBO-FRODO

[21,22], and the structures were further refined with the X-PLOR

program (version 3.1) for the energy minimization (see details in [23,24]).

Some atomic distances and other molecular details were determined with

the WebLab ViewerPro software from Molecular Simulations Inc. (San Diego,

CA). Other calculations were performed with Maple (version V) from

Waterloo Maple Inc. (Waterloo, ON), and Origin (version 5) from Microcal

Software, Inc. (Northampton, MA).

3.1. Molecular structure of the docked interface in cyt f-pc

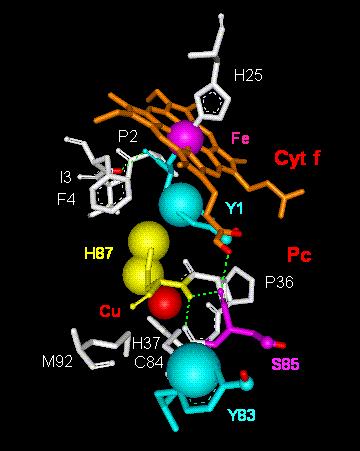

The structural representation of the cyt f and pc redox

partners in the cyt f-pc docked complex is displayed in Fig. 1.

This structure was obtained from a series of modellizations performed according

to the procedures which are described above (see Methodology). The

analysis of the structures represented in Fig. 1 [A. Kajava, M.

Fragata, in preparation] disclosed some predominant molecular details

in the docked surfaces of cyt f and pc such as the ionic bonds and charge

interactions on the one hand, and the hydrophobic contacts on the other

hand. The most important molecular details are summarized in the

Table

1. That is, a positively charged cluster and a non-polar surface

around Tyr 1 in cyt f (i, ii), and two negatively charged clusters

and a non-polar surface surrounding the copper-atom in pc (iii, iv).

Fig. 1. Molecular

detail of the structural sites of oxidation-reduction in the complexes

between cytochrome f and plastocyanin (cyt f-pc).

In

order to facilitate their visualization,

the heme macrocycle in cyt f and the copper-atom in pc are drawn

in 'ball and stick' sizes higher

than in the surrounding amino acid residues. Color code:

light blue, iron-atom in cyt f; red,

copper-atom in pc; yellow, heme macrocylce in cyt f.

| cyt f pc |

(i) Positively charged

cluster constituted of

Lys58,a Lys65, Lys185, Lys187, Arg209 (ii) Non-polar surface around Tyr 1 including Iso3, Phe4, Leu61, Ala62, Pro117, Tyr160, Pro161 (iii) Two negatively charged clusters constituted

of

|

top

3.2. Structural

pathways of electron transfer in cyt f-pc

In higher plants chloroplasts the cytochrome b6f (cyt b6f)

complex transfers electrons between the photosystem II complex and the

P700 reaction center in the photosystem I (PSI) complex. From cytochrome

f (cyt f) in cyt b6f to PSI, the electrons are shuttled by the mobile redox

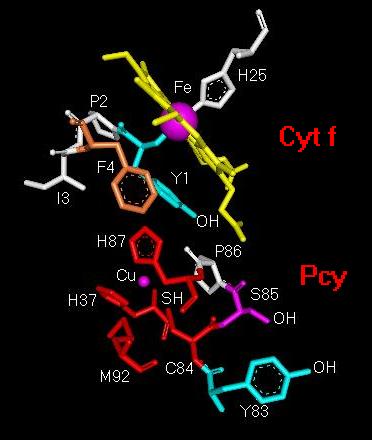

carrier plastocyanin (pc) [3-6]. Fig. 2 shows a detail

of the electron transfer interface in the cyt f-pc complex obtained from

molecular modelling of the cyt f-pc interaction. In short, electron

tranfer between the Fe-atom in the cyt f heme and the tyrosine 83 (Y83)

in plastocyanin starts with the oxidation of the Fe-atom and electron transfer

directly to the OH group or the pi-electron system of tyrosine 1 (Y1) in

cyt f, or through an intermediate pyrrole ring in the cyt f heme macrocycle.

From there, the electron transfer route goes through the Cu-coordination

centre following most likely one or several molecular pathways.

Fig. 2. Structural

detail of the molecular electron-transfer pathway from

the Fe-atom in cytochrome f (Cyt f)

to tyrosine 83 in plastocyanin (Pcy).

Abbreviations: Cu, copper atom in Pcy; C84, cysteine

84; Fe, iron atom in cyt f

heme; F4, phenylalanine 4; H25, histidine 25; H37, histidine

37; H87, histidine

87; I3, isoleucine 3; M92, methionine 92; P2, proline

2; P86, proline 86; S85,

serine 85; Y1, tyrosine 1; Y83, tyrosine 83.

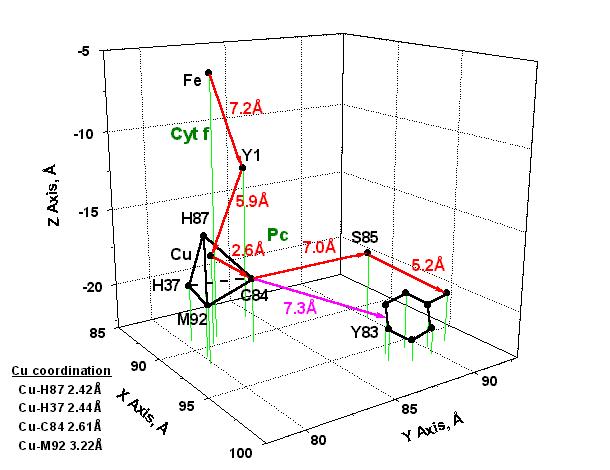

A schematic representation of the distances between the amino acid residues that most likely participate in electron transfer in the cyt f-Pc complex is given in Fig. 3. The figure shows that the distance from the Fe-coordination centre to Y1 is approximately 7.2 Å and 5.9 Å from Y1 to the Cu-ion. From C84(SH) to S85(OH) and from S85(OH) to Y83(OH) the electron transfer distances are respectively about 7.0 Å and 5.2 Å. The figure indicates also that another possible electron transfer route is between C84(SH) and the p-electron system in Y83 with an interaction distance of the order of 7.3 Å. This interesting since it has been emphasized in past discussions that electron transfer distances higher than about 5 Å are a reliable indication of electron transfer occurring by tunnelling efffect, that is, by a quantum jump from one electronic state to another (see, e.g., [1]).

Fig. 3. Model of electron transfer from the

Fe-coordination centre in cytochrome f

(Cyt f) to the Cu-coordination centre and

tyrosine 83 in plastocyanin (Pc).

The

X, Y, Z

coordinates were obtained from the pc structure shown in Fig. 1.

The most probable pathways

of electron transfer are shown with red

arrows;

another possible route of electron transfer

between C84 and the p-electron system in Y83

is indicated with a magenta arrow.

Abbreviations:

Cu, copper ion in Pc; C84, cysteine 84;

Fe, iron ion in cyt f heme; H37,

histidine 37; H87, histidine 87; M92, methionine 92;

S85, serine 85; Y1, tyrosine 1;

Y83, tyrosine 83.

Fig. 3 indicates also

that the distance Cu-C84(SH) is approximately 2.6 Å, i.e., the coordination

distance from the Cu-ion to the SH group in C84. This is a quite

small electron transfer distance in relation to the 5 to 7 Å determined

for the other pathways illustrated in the figure. At first,

this is a convincing argument to suggest the co-existence of different

molecular mechanisms of electron transfer in the Cyt f-Pc complex.

Secondly, an electron transfer distance of about 2.6 Å is a good

indication that in the Cu-coordination centre, and maybe also in its molecular

nearness, the electron transfer reaction originates in van der Waals (vdW)

contacts. This question is discussed further in section (ii) below.

Fig.

3 indicates also that the Cu-ion in pc is coordinated to the

cysteine 84 (C84) thiol group, the methionine 92 (M92) thioether

group, and the histidines 37 (H37) and 87 (H87) imidazole groups in

a quite highly distorted tetrahedral configuration. The corresponding

coordination distances are given in the figure. Such unstable

three-dimensional configuration has partly its origin in differences of

conformational strain energy (DHs) of the amino

acid residues (see discussion in [25]) in the Cu-coordination centre.

That is, DHs = 0.08 (C84), 11.68 (M92)

and 14.15 (H37, H87) kJ/mol. This materializes in the almost identical

coordination distances for Cu-H87 (2.42 Å), Cu-H37 (2.44 Å)

and Cu-C84 (2.61 Å) as compared to the quite different Cu-M92 distance

(3.22 Å) which gives thus rise to the distortion observed in the

coordination tetrahedron.

The distorted tetrahedral configuration of the Cu-coordination

centre is obviously unstable from a thermodynamic viewpoint, inusmuch as

the copper ion may adopt two different configurations; that is, the

configurations corresponding to the coordination numbers (CN) four or six

(see, e.g., [26]). It is worth noting at this point that a

fifth and a sixth coordination partners corresponding to CN = 6 are predicted,

in addition to the more common four coordination partners of the Cu-ion

in pc which are usually identified with the amino acid residues described

above. The implicit fifth and sixth coordination partners were not,

however, correctly identified. Nevertheless, this matter raises an

interesting point. In fact, the crystal radii for the Cu-ion being

0.74 Å for CN = 4 and 0.91 Å for CN = 6 [26], it becomes

perceptible that any molecular volume change in the Cu-centre should

have functional consequences that have not yet been determined, but which

are certainly instrumental in influencing the electron transfer rate in

cyt f-pc, at least in the route from the Cu-ion to Y83. This may

take place, for example, by changing the arrangement and the reorganizational

energy [1] of the van der Waals contacts in the region comprising

the H87

imidazole ring, the Cu-ion and the C84 thiol group. This means

that supplemental electron transfer-induced dynamical distortion of the

already distorted tetrahedron shall thereby create an oscillatory unstable

state upon electron transfer that may render the copper coordination center

a highly unstable region of the plastocyanin molecule which is exactly

what is suitable for rapid electron transfer excursion sequences.

top

3.3.

Intramolecular electron transfer: Tunnelling effect

The theoretical prediction of the

probability of an electron penetrating an energy barrier, that is, the

electron tunnelling through a barrier has been tried in many previous works

(see discussions in [1,2]). Various mathematical expressions

were used to determine the

tunnelling rate constant [1,2,27-37],

kd (in s-1). However, comparison of the theoretical

results with experimental data showed that quite often that the observed

results are usually smaller, sometimes by several orders of magnitude,

than those predicted by theory. For

example, the rate constants of plastocyanin reduction

were shown to be in most cases between about 2800 and 8200 s-1

(see, e.g., [31,38,39]), whereas the values obtained theoretically

are generally much higher. These discrepancies stem partly from the

complex structure of the molecular pathway followed by the electron in

its flight from the electron donor site (EDS) to the acceptor site (EAS).

Additional complications result from the dynamical changes accompanying

the electron transfer either at EDS or at EAS, or in-between, which obviously

change the energy states of the various molecular steps in the structural

pathway of electron transfer. These questions have been approached

in some instances (see discussions on, e.g, the energy of reorganization

in [1,2]), but so far the mathematical expressions of kd

are not yet completely adequate to give a reasonable fit between theory

and experiment. The modification of the mathematical expressions

of kd to include the structural and molecular dynamics parameters

above mentioned is an interesting task that deserves to approached in future

works. This may be achieved using, for example, the new methods

of the knowledge-based models of simulate the redox proteins core at the

molecular sites, or regions, where an electron in a local pool of 'nEDS

electrons' is displaced to a pool of 'mEAS electrons'

by either a non-adiabatic (e.g., a tunnelling jump) or an adiabatic process

of the kind extensively discussed in [1,2,40].

In spite of the afore discussed difficulties, most of the theoretical expressions mentioned in [1,2,27-37] were shown to be instrumental in the study of several aspects of the electron tunnelling in proteins involved in biological oxidation-reduction, and also in electron trasfer reactions via Van der Waals molecular contacts. In this work , the tunnelling rate constant, kd , for a one-dimensional square barrier was determined according to the expression of McElroy et al. [30] (eq. 1).

kd = [16E2(V-E)/hV2] exp{-2p[8m(V-E)]1/2/h]d} eq. 1

where h is Planck's constant, m the mass of the electron, V the barrier height above the electron energy, i.e., potential energy of the electron inside de barrier, E the kinetic energy of the approaching electron (outside the barrier), and d the tunnelling distance. In eq. 1, kd is the probability of an electron crossing the barrier by tunnelling, and in such sense it is the tunnelling rate constant given in s-1. Eq. 1 was transformed to give the values of kd as a function of V, dV (= V-E) and d, for a particular electron transfer pathway. Taking into account that h = 6.626196 x10-34 J.s, m = 9.109558 x 10-31 kg, d is given in Å units, and E, V and dV are given in eV, one has

kd = 3.863 x 1015 [1-(dV/V)]2dV exp[-1.026(dV1/2)d] eq. 2

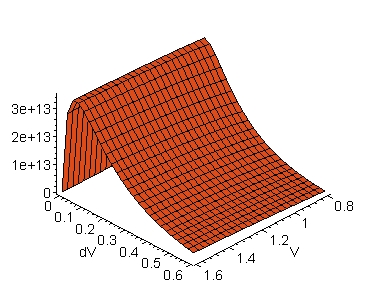

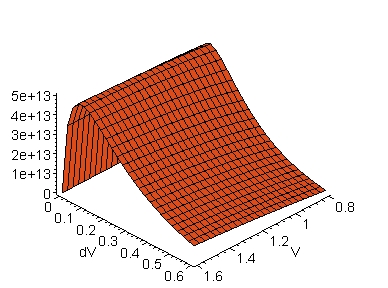

The evolution of kd as a function of concomitant variations of dV and V is seen in the three-dimensional graphical representations displayed in Fig. 4. To construct the graphs in this figure, the distances d determined in Fig. 2 were used, that is, d = 7.2 Å in the electron transfer route from the iron-atom to the tyrosine 1 (Y1) in cytochrome f, i.e., the Fe(cyt f) ® Y1-OH(cyt f) route (A), and d = 5.9 Å in the electron transfer route from Y1 to the copper-atom in platocyanin, i.e., the Y1-OH(cyt f) ® Cu(pc) route (B).

A: Fe(cyt f) ® Y1-OH(cyt f) B: Y1-OH(cyt f) ® Cu(pc)

Fig. 4. Tunnelling rate constant, kd (in

s-1), along the structural pathways of electron transfer in

the cytochrome f-

plastocyanin complex. The Y axes are the tunnelling rate

constants calculated according to eq. 2 (see text). The distances,

d (in Å),

between the electron donor-acceptor sites were obtained from the molecular

coordinates of the cyt f-pc complex as is shown in Fig. 3;

d is 7.2 Å in the Fe(cyt f) ®

Y1-OH(cyt

f) route (A), and 5.9 Å

in the Y1-OH(cyt f) ® Cu(pc)

route

(B). Abbreviations:

cyt f,

cytochrome f; Cu(pc), copper-atom in pc; Fe(cyt f), iron-atom

in cyt f; pc, plastocyanin; Y1, tyrosine 1.

An interesting observation in Fig. 4 is that the

kd maxima are observed for dV's of the order of 0.1 eV for any

V in the range from 0.8 to 1.6 eV. This is aggreement with the notion

that the energy differences between V and E (= dV) might, in general, be

small (see, e.g., [2]). It is important to note, however,

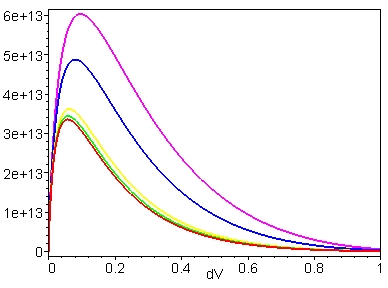

that the dV value at kd maximum, dVkd(max), decreases

with d (Fig. 5) according to an exponential decay as is seen in

Fig.

6. This is also illustrated below in eq. 3.

Fig. 5. Tunnelling rate constant, kd (in

s-1), as a function of dV for the structural pathways

of electron transfer in the cytochrome f-plastocyanin complex. The

Y

axis is the tunnelling rate

constant calculated according to eq. 2 (see text). The distances,

d (in Å), between the electron donor-

acceptor sites were obtained from the molecular coordinates of the cyt

f-pc complex as is shown in

Fig. 3. Color code for the distances d: magenta,

5.2 Å; blue, 5.9 Å; yellow,

7.0 Å; green, 7.2 Å;

red, 7.3 Å. Abbreviations: cyt f, cytochrome

f; pc, plastocyanin.

Fig. 6. dV (in eV) at the kd maximum

(in s-1) as a function of d (in Å). dV

is given by the expression

dV=0.011 + 0.167exp[-(d-2)/3.786]. The dV's (dV=V-E) and the distances,

d (in Å), between the electron

donor-acceptor sites and were were calculated according eq.

2 (see text). Abbreviations: cyt f, cytochrome

f;

d, tunnelling distance; dV=V-E; E, kinetic energy of the electron

approaching the barrier; kd, tunnelling rate

constant; pc, plastocyanin; V, barrier height above the electron

energy.

The exponential decay of dVkd(max) with increasing d (Fig. 6) is represented by the expression

dVkd(max) = 0.011 + 0.283exp(-0.264d), eq. 3

The limiting values in eq. 3 are

0.294 eV > dVkd(max) > 0.178 eV, for

d < 2 Å,

0.178 eV > dVkd(max) > 0.011 eV, for

2 Å < d < ~20-30 Å, and

dVkd(max) ~ 0.011 eV, for

d > ~20-30 Å.

An interesting point in this respct is that at short distances

between the electron donor and acceptor sites, the dVkd(max) difference

may take much larger values than the dVkd(max) differences for

donor and acceptor sites separated by large distances, where dV has to

be small for an efficient electron transfer to take place. In other

words, an efficient electron transfer at the most usual tunnelling distances,

i.e., from 5 to 10 Å (see, e.g., [1]), implies that the energy

of the electron approaching the tunnelling barrrier, E, must be close to

the energy of the tunnelling barrier, V, or almost identical (see discussions

in [2]).

top

3.4. Intramolecular electron

transfer: Van der Waals contact

From the above considerations, it is reasonable to foresee

that the transfer of an electron from Y1 (in cyt f) to the Cu-ion in plastocyanin,

the bond lengths in the Cu-coordination centre must distort from their

steady-state geometry, or quasi-equilibrium condition, to a distorted

geometry, or transition-state geometry, where lenghtening and contraction

of bonds might occur. For this to take place, energy is expended

prior to the return of the coordinnation centre to its equilibrium geometry.

A structural model to take these effects into account is presented in Fig.

7.

Fig. 7. Model of electron transfer via van der

Waals contacts throughout

tyrosine 1 in cytochrome f (Cyt f) to histidine

87 and the Cu-atom in plastocyanin

(Pc). Abbreviations:

Cu,

copper atom in Pc; C84, cysteine 84; Fe, iron atom in cyt f

heme; F4, phenylalanine 4; H25, histidine 25; H37, histidine

37; H87, histidine 87;

I3, isoleucine 3; M92, methionine 92; P2, proline 2;

P36, proline 36; S85, serine 85;

Y1, tyrosine 1; Y83, tyrosine 83.

Fig. 7 shows the most likely 'van der Waals routes' (vdW1,vdW2) together with the 'tunnelling pathways' (T1-T3) discussed above (Figs. 2 and 3). A summary is given in Scheme I with indication of the respective tunnelling or van der Waals distances in square brackets (cf. also Fig. 3):

| vdW1: Y1(cyt f)®H87(pc)

[... Å]

H87(pc)®Cu(pc) [... Å] vdW2: Cu(pc)®C84(pc) [2.6 Å] |

| T1: Fe(cyt

f)®Y1-OH(cyt f) [7.2 Å]

Y1-OH(cyt f)®Cu(pc) [5.9 Å] T2: C84(pc)]®S85(pc) [7.0 Å] S85(pc)®Y83-OH(pc) [5.2 Å] T3: C84(pc)]®Y83[p-electron system](pc) [7.3 Å] |

Now, the various structural rearrangements and molecular dynamics in these intramolecular pathways during electron transfer from the iron-atom in cytochrome f to the copper-atom in plastocyanin are certainly at least some of the factors that may have to taken into account for the correction of mathematical expressions of kd as, for example, McElroy et al.'s equation [30] used in this work (eq. 1). A reasonable correction, although empirical at this stage, would be to multiply kd by an appropriate scale factor, f, that is,

kd = [16E2f(V-E)/hV2] exp{-2p[8m(V-E)]1/2/h]d} eq. 4

For example, an appropriate accord between the theoretical and experimental kd's for the reduction of plastocyanin by cytochrome f would be obtained for f values from 0.5 to 20 x 10-10, meaning that eq. 2 would take the lower and upper limits represented by eqs. 5 and 6, that is,

kd = 1.931 x

105 [1-(dV/V)]2dV exp[-1.026(dV1/2)d]

eq. 5

and kd = 77.260 x

105 [1-(dV/V)]2dV exp[-1.026(dV1/2)d]

eq. 6

This would yield kd(max) between 2200 and 84000 s-1

(cf., in this respect, [31,38,39]) for barrier heights, V, and tunnelling

distances, d, of the order of 0.8 eV and 6 Å, respectively.

It is acknowledge, however, that it is not yet possible to correlate this

still empirical correction to the molecular dynamics (e.g., structural

rearrangements and/or side chains movements) of electron transfer occurring

at the docking interfaces or inside the protein core of two biological

redox macromolecules, here the cytochrome f and plastocyanin molecules.

top

4. Concluding remarks

First, the data shown in Figs. 2, 3 and 7 indicate that different electron transfer mechanisms may take place in the same cyt f-pc complex, that is, electron transfer by tunnelling effect and via van der Waals molecular contacts. This may have far reaching consequences since, in a first approximation, it presupposes the parallel function of adiabatic and non-adiabatic electron transfer processes, thereby implying the interplay of mechanisms with different temperature dependence, or requirements [1,2]. The coexistence of the tunnelling effect and the Van der Waals contacts in the same electron transfer rapid pennetrative excursion may well constitute a means of control of the physiological function of the cyt-Pc complex, but also of the electron transfer reactions between the cytochrome b6f complex and P700, i.e., the reaction center of photosystem I in the photosynthetic membrane.

Secondly, another question still remaining is the possibility that water molecules, or the displacement of hydrogen ions, may provide an efficient mechanism and pathway of electron transfer (see discussions in [40,41]). In which the cyt f-Pc complex is concerned, the mediation or facilitation of electron transfer by interposed water molecules inside the protein complex is an assumption that, though attractive, has most probably to be ruled out on account of arguments discussed in computer simulations of water-plastocyanin interaction energies [42]. Nevertheless, a recent work of Sainz et al. [43] shows that (i) an internal chain of five H2O molecules in the protein core of cyt f near the heme macrocycle just before the docking interface is important to its function, and (ii) the perturbation of this chain of water molecules impairs the cytochrome f function. In addition, there is evidence indicating that proton transfer to a buried redox center in proteins is a type of mechanism that may be instrumental in electron transfer [44].

Finally, it is implicit in the pathways schematized

in Figs. 2 and 7 that one needs to

modify the mathematical expressions of kd (eqs. 1-4)

in order to include structural and molecular dynamics parameters such as,

e.g., the effect of

side chain movements on electron transfer through

'electron transfer holes' such as those in the cyt f-pc complex.

This is an interesting task that shall be undertaken

using, for example, knowledge-based models (see recent work

in [45]) to simulate the molecular core of the redox proteins at

the sites, or molecular domains, where the electron displacements take

place by either non-adiabatic tunnelling jumps or van der Waals processes

[1,2,46].

top

5. Abbreviations

| cyt b6f

cyt f d dV dVkd(max) E kd pc P700 PSI PSII V vdW |

cytochrome b6f

cytochrome f distance between the electron donor and acceptor sites (in Å) = V - E (in eV) dV at the kd maximum (in eV) [cf. eqs. 4 and 5] kinetic energy of the electron approaching the barrier (in eV) tunnelling rate constant (in s-1) plastocyanin reaction center in PSI photosystem I photsystem II barrier height above the electron energy (in eV) van der Waals |

top

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by grant OGP0006357 from the Natural

Science and Engineering Research Council of Canada and institutional grants

from the Université du Québec à Trois-Rivières,

and is the result of a collaboration with Dr. A. Kajava at the Institut

Suisse de Recherches Expérimentales sur le Cancer (ISREC), Groupe

de Bioinformatique, Epalinges s/Lausanne, Suisse. I wish to thank

Dr. A. Kajava and the Bioinformatics Group and Library staff at ISREC for

the friendliness of their welcome and help. Last but not least, I

am very grateful to Dr. I. Gabashvili for the many clever comments and

suggestions made during the preparation of this work.

[ 1] D. DeVault, Quantum-mechanical Tunnelling in Biological

Systems, 2nd ed., Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1984.

[ 2] R.A. Marcus, N. Sutin, Electron transfer in chemistry

and biology, Biochim. Biophys. Acta 811 (1985) 265-322.

[ 3] H. Bohner, H. Böhme, P. Böger, Reciprocal

formation of plastocyanin and cytochrome c-553 and the influence of cupric

ions on

photosynthetic electron

transport, Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 592 (1980) 103-112.

[ 4] G. Sandmann, Reck., E. Kessler, P. Böger, Distribution

of plastocyanin and soluble plastidic cytochrome c in various classes of

algae,

Arch. Microbiol. 134

(1983) 23-27.

[ 5] K.K. Ho, D.W. Krogmann, Electron donors to P700 in

cyanobacteria and algae. An instance of unusual genetic variability,

Biochim.

Biophys. Acta. 766

(1984) 310-316.

[ 6] H. Zhang, H.B. Pakrasi, J. Whitmarsh, Photoautotrophic

growth of the cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. PCC6803 in the absence of

cytochrome c553 and

plastocyanin, J. Biol. Chem. 269 (1994) 5036-5042.

[ 7] G. Sandmann, P. Böger, Physiological factors

determining the formation of plastocyanin and plastidic cytochrome c-553

in

Scenedesmus, Planta

147 (1980) 330-334.

[ 8] S. Merchant, L. Bogorad, Metal ion regulated gene

expression: use of a plastocyanin-less mutant of Chlamydomonas reinhardtii

to

study the Cu(II)-dependent

expression of cytochrome c-552, EMBO J. 6 (1987) 2531-2535.

[ 9] C. Frazão, C.M. Soares, M.A. Carrondo, E. Pohl,

Z. Dauter, K.S. Wilson, M. Hervás, J.A. Navarro, M.A. De la Rosa,

G.M. Sheldrick, Ab

initio determination

of the crystal structure of cytochrome c6 and comparison with plastocyanin,

Structure 3 (1995) 1159-1169.

[10] E.L. Gross, Plastocyanin: structure, location, diffusion,

and electron transfer mechanisms. in: D. Ort, C. Yokum (Eds.), Oxygenic

Photosynthesis:

The Light Reactions, Kluwer Academic Publishers, Dordrecht, The Netherlands,

1996, pp. - .

[11] T. Takabe, H. Ishikawa, S. Niwa, Y. Tanaka, Electron

transfer reactions of chemically-modified plastocyanins with P700 and

cytochrome f,

J. Biochem. (Tokyo) 96 (1984)385-393.

[12] G.P. Anderson, D. G. Sanderson, C. H. Lee, S. Durell, L.

B. Anderson, E. L. Gross, The effect of ethylenediamine chemical

modification of plastocyanin

on the rate of cytochrome f oxidation and P700 reduction, Biochim. Biophys.

Acta 894 (1987) 386-396.

[13] L.Z. Morand, M.K. Frame, K.K. Colvert, D.A. Johnson, D.W.

Krogman, D.J. Davis, Plastocyanin-cytochrome f interaction,

Biochemistry 28 (1989)

8039-8047.

[14] T. Takabe, H. Ishikawa, Kinetic studies on a cross-linked

complex between plastocyanin and cytochrome f, J. Biochem. (Tokyo) 105

(1989) 92-102.

[15] S. Modi, S. He, J.C. Gray, D.S. Bendall, The role of surface

exposed tyr-83 of plastocyanin in electron transfer from cytochrome c,

Biochim. Biophys.

Acta. 1101(1992) 64-68.

[16] S. Modi, M. Nordling, L.G. Lundberg, Ö. Hansson, D.S.

Bendall, Reactivity of cytochromes c and f with mutant forms of spinach

plastocyanin, Biochim.

Biophys. Acta 1102 (1992) 85-90.

[17] L. Qin, N.M. Kostic, Importance of protein rearrangement

in the electron-transfer reaction between the physiological partners

cytochrome f and plastocyanin,

Biochemistry 32 (1993) 6073-6080.

[18] T.B. Karpishin, M.W. Grinstaff, S. Komar-Panicucci, G. McLendon,

H.B. Gray, Electron transfer in cytochrome c depends upon the

structure of the intervening

medium, Structure 2 (1994) 415-422.

[19] F.C. Bernstein, T.F. Koetzle, G.J.B. Williams, E.F. Meyer,

M.D. Brice, J.R. Rogers, O. Kennard, T. Shimanouchi, M. Tatsumi, The

Protein Data Bank:

a computer-based archival file for macromolecular structures, J. Mol. Biol.

112 (1977) 535-542.

[20] H.M. Berman, J. Westbrook, Z. Feng, G. Gilliland, T.N. Bhat,

H. Weissig, I.N. Shindyalov, P.E. Bourne. The Protein Data Bank,

Nucleic Acids Res.

28 (2000) 235-242.

[21] A. Roussel, C. Cambillan, In Silicon Graphics Geometry Partner

Directory (Fall 1989), Silicon Graphics, editor, Silicon Graphics,

Mountain View, CA.

pp 77-78.

[22] A. Roussel, A.G. Inisan, TURBO-FRODO, Version 4.3, release

a. Bio-Graphics, Marseille, France, 1993.

[23] A.T. Brunger, X-PLOR Version 3.1: A System for X-Ray Crystallography

and NMR. Yale University Press, New Haven, CT, 1992.

[24] A.V. Kajava, Modeling of a five-stranded coiled coil structure

for the assemby domain of the cartilage oligomeric matrix protein,

Proteins: Structure,

Function and Genetics 24 (1996) 218-226.

[25] K. Sak, M. Karelson, J. Jarv, Bioorg. Chem. 27 (1999) 434-442.

[26] B. Douglas, D.H. McDaniel, J.J. Alexander, Concepts and

Models of Inorganic Chemistry, 2nd ed., John Wiley, New York, 1983.

[27] D. DeVault, B. Chance, Biophys. J.

6 (1966) 825-.

[28] T. Kihara, B. Chance, Cytochrome photooxidation

at liquid nitrogen temperatures in photosyhthetic bacteria, Biochim. Biophys.

Acta

189 (1969) 116-124.

[29] J.J. Hopfield, Electron transfer between

biological molecules by thermally activated tunneling, Proc. Nat. Acad.

Sci. USA 71 (1974)

3640-3644.

[30] J.D. McElroy, D. Mauzerall, G. Feher,

Characterization of primary reactants in bacterial photosynthesis.

II. Kinetic studies of the

light-induced EPR signal (g = 2.0026) and the optical absorbance changes

at cryogenic temperatures, Biochim. Biophys. Acta 333

(1974) 261-177.

[31] M. Fragata, F. Bellemare, Dielectric

constant dependence of biological oxidation-reduction. 1. A model

of polarity-dependent

ferrocytochrome c oxidation, Biophys. Chem. 15 (1982) 111-119.

[32] G. McLendon, R. Hake, Interprotein

electron transfer, Chem. Rev. 92 (1992) 481-490.

[33] J.M. Nocek, J.S. Zhou, S. De Forest,

S. Priyadarshy, D.N. Beratan, J.N. Onuchic, B.M. Hoffman, Theory and practice

of electron

transfer within protein-protein complexes: application to the multidomain

binding of cytochrome c by cytochrome c peroxidase,

Chem. Rev. 96 (1996) 2459-2489.

[34] A.J.A. Aquino, P. Beroza, J. Reagan,

J.N. Onuchic, Estimating the effect of protein dynamics on electron transfer

to the special pair in

the photosynthetic reaction center, Chem. Phys. Let. 275 (1997) 181-187.

[35] M.R. Haris, D.J. Davis, B. Durham,

F. Millett, Temperature and viscosity dependence of the electron-transfer

reaction between

plastocyanin and cytochrome c labeled with a ruthenium(II) bipyridine complex,

Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1319 (1997) 147-154.

[36] C.A. Cunha, M.J. Romão, S.J.

Sadeghi, F. Valetti, G. Gilardi, C.M. Soares, J. Biol. Inorg. Chem. 4 (1999)

360-374.

[37] G.N. Chuev, V.D. Lakhno, M.N. Ustitnin,

Superexchange coupling and electron transfer in globular proteins via polaron

excitations,

J. Biol. Phys. 26 (2000) 173-184.

[38] L. Qin, N.M. Kostic, Importance of

protein rearrangement in the electron-transfer reaction between the physiological

partners

cytochrome f and plastocyanin, Biochemistry 32 (1993) 6073-6080.

[39] Y. Ilan, A. Shafferman, Biochim. Biophys. Acta 501 (1978

127.

[40] S.T. Prigge, A.S. Kolhekar, B.A. Eipper, R.E. Mains, L.M.

Amzel, Nature Struct. Biol. 6 (1999) 976-983.

[41] G.N.R. Tripathi, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 120 (1998) 4161-4166.

[42] C.X. Wang, S. Cannistraro, Il Nuovo Cimento 5 (1985) 405-414.

[43] G. Sainz, C.J. Carrell, M.V. Ponamarev, G.M. Soriano, W.A.

Cramer, J.L. Smith, Interruption of the internal water chain of

cytochrome f impairs

photosynthetic function, Biochemistry 39 (2000) 9164-9173.

[44] K. Chen, J. Hirst, R. Camba, C.A. Bonagura, C.D. Stout,

B.K. Burgess, F.A. Armstrong, Atomically defined mechanism for proton

transfer to a buried

redox centre in a protein, Nature 405 (2000) 814-817.

[45] J. Xiong, S. Subramaniam, Govindjee, Aknowledge-based three

dimensional model of the Photosystem II reaction center of

Chlamidomonas reinhardtii,

Photosynth. Res. 56 (1998) 229-254.

[46] M.V. Volkenstein, General Biophysics,

Vol. II, Academic Press, New York, 1983.

| Mário Fragata

fragata@uqtr.uquebec.caNovember 14, 1967 to gsi at 8:15am |